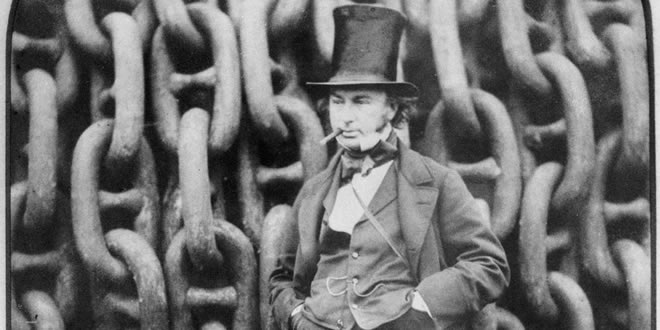

The Engineering Life and Times of Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Lauded as one of the most visionary,audacious, versatile engineering geniuses that ever lived, Isambard Kingdom Brunel is one of the most famous Victorian engineers responsible for the design of tunnels, bridges, railway lines and ships. He is often deemed as the revolutionary icon who built Britain. He built under rivers and through hills, creating the longest tunnels, the biggest bridges and the speediest ships the world had ever seen at that time. By the time of his death at 53, Brunel had made a major impact on Victorian civil engineering with projects including the Great Western Railway, the Clifton suspension bridge, and transatlantic steamships.

Early Life

Born on April 9, 1806, Isambard Brunel Kingdom was born to an English mother, Sophia Kingdom and a French civil engineer, Marc Isambard Brunel. Though a great engineer, his father was not good at managing finances and even spent three months in a debtor’s prison. However, his inventive nature rubbed off on his son, who was fluent in French and had a command over geometry and draughtsmanship by the age of eight. He was sent to France at the age of 14 to study mathematics.

The Thames Tunnel

Isambard returned to England after his studies and went to work for his father. He embarked on his first engineering project, building the Thames Tunnel from Rotherhithe to Wapping in east London. Still part of the London subway system today, this project was quite dangerous and way ahead of its time. It was the first tunnel under a river anywhere in the world at the time and Marc Brunel had invented a tunnel shield to ensure the success of this project. The shield was rectangular and had 12 digging positions across its width and three digging positions on top of each other so allowing 36 miners to work simultaneously. The Thames Tunnel was dug a few inches at a time, 1,200 feet across the River Thames. The workers faced many challenges: appalling air quality, constant seeping water from the River Thames and sewage entering the tunnel, giving off methane gas. Tunnel foods were a common occurrence and on one occasion six men are swept to their deaths in a tidal wave of sewage, debris and water. Isambard Kingdom Brunel was almost killed had it not been for one of his assistants who managed to pull his unconscious body from the water. Thereafter, work stopped on the tunnel for six years for lack of financing. When the Tunnel finally opened to the public in 1843, it was instantly dubbed the Eighth Wonder of the World, attracting thousands of people. Marc Brunel was knighted by Queen Victoria for this feat. It was the first and last project father and son would work on together. Despite the challenges faced, the Tunnel is still one of the most watertight tunnels on the London underground system.

The Clifton Suspension Bridge

While he was recuperating from his accident at the Thames Tunnel, Isambard heard about a competition to design a bridge over the River Avon. At the time it was the longest bridge in the world, spanning 76m deep gorge with sheer rock on either side. His original design was rejected on the advice of Thomas Telford, often described as the godfather of civil engineering and Isambard’s rival. Finally, an improved version that featured Egyptian-influenced sphinxes and hieroglyphs was accepted. Unfortunately, Isambard never got to see the completion of one of his greatest achievements. Work on the bridge stopped due to riots and was eventually abandoned due to a lack of funds. It was not completed until 1864, after Isambard’s death.

Great Western Railway

At the age of 27, Isambard was appointed the chief engineer for the work on the Great Western Railway linking Bristol and London. Some of his greatest achievements during the construction of this railway include viaducts at Hanwell and Chippenham, the Maidenhead Bridge, the Box Tunnel and Bristol’s Temple Meads Station. Renowned for his eye for detail, Isambard left nothing to chance; everything from lampposts, stations, locomotives, carriages and even the width of the track were re-designed. He used the broad gauge (2.2m) instead of standard gauge (1.55m). While this produced a smoother, faster journey it also meant passengers had to change trains at stations where the two gauges met. The Maidenhead Bridge is still the widest, flattest brick arch bridge in the world. Then the longest railway tunnel in existence, the Box Tunnel took 5 years to complete and 4000 men with dynamite to build it.

The Great Western

Isambard persuaded the company which backed the Great Western Railway to consider trans-Atlantic travel. He designed a grand steamship, the Great Western, which was the first of ‘the Three Great Ships’ of Isambard Kingdom Brunel. The ship had paddlewheels rather than propellers, and four masts to hoist sails. Though built of wood, it contained a powerful steam engine, and it was designed specifically to cross the rough North Atlantic. The Great Western made her first voyage in 1838, a journey that took 15 days. The largest vessel in the world at that time, it was the first steamship to engage in transatlantic service. During her launch, Isambard was badly burnt during an engine fire and had to be put ashore at Canvey Island.

Other Works

Isambard was also responsible for the redesign and construction of many of Britain’s major docks, including Bristol, Monkwearmouth, Cardiff and Milford Haven. He also built the first prefabricated modern hospital during the Crimean War, Renkioi Hospital. Isambard worked on other steamships as well. The SS Great Britain was launched in 1843 and was the largest ship in the world. A revolutionary vessel and fore-runner of all modern shipping, the SS Great Britain was the first screw-propelled, iron-hulled steam ship. It marked the beginnings of international passenger travel and world communications. Isambard’s final project, the Great Eastern, was built to transport 4,000 passengers between London and Sydney, Australia. Unfortunately it encountered a series of engineering problems and was way ahead of its time. Attempts to find a purpose for this ship failed and it was eventually sold for scraps. Many believe that the stress of his final project is what eventually led to the death of Isambard Kingdom Brunnel.

Death

Isambard suffered a stroke after hearing the news of an explosion on board the Great Eastern during her sea trials and died on 15 September 1859. Five days later Isambard Kingdom Brunel was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery in London.